News

Three Days in Raiford Prison ~ 1939

Wednesday, September 2, 2020

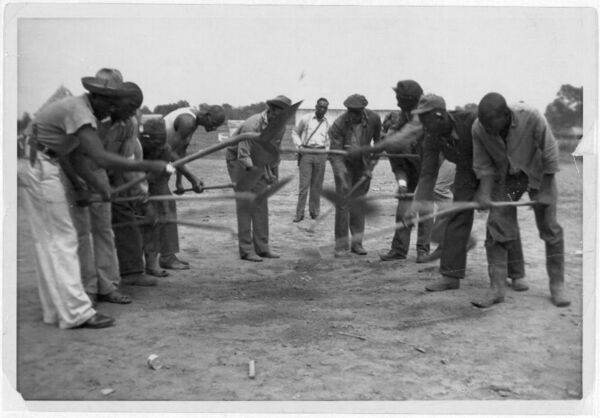

Prisoners in SC (not FL) - late 1930s

The Lineage of a Song: John A. Lomax, Ruby Terrill Lomax

& The Archives of American Folklife Center

Copyright 2020 Joe Jencks, Turtle Bear Music

Please Note: Following this article are additional Lyrics & Notes for all five songs I ressurrected from the archives of The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, for the 2020 Homegrown at Home virtual concert series.

We Don't Have No Payday Here

Touble Is Hard

Oh, Ye Prodigal Son

Battle Ax

Take 'Dis Hammer

You can listen to the "concert" here:

https://www.loc.gov/concerts/folklife/joe-jencks.html

I have on several occasions been asked to be a part of the Library of Congress, Folk Archives Challenge at the Folk Alliance International Conference. It’s always an honor and a good time. It is fun, relaxed, musically interesting and always educational. Musicians from all over the US and a few from other countries dive into the L.O.C. Folk Archives and resurrect some song that has fallen by the wayside. Or they render a new version of an old chestnut, and in so doing help us hear an old song in a new way. I always enjoy the concert that is assembled from musicians who have chosen to participate. It never fails to enlighten and delight.

I have to admit in all honesty that at least once, I trolled the archives for songs I already knew, and picked one of them. Based on looking at people’s albums/ song titles and comparing that to what was performed in concerts at the conference, I am clearly not the only one who has taken the road more traveled now and then.

But this year, this year I dove deep. I looked through dozens of songs and went deep down the rabbit hole of songs relating to work and chain gangs in the south, and prison yard songs. And the song I emerged with was, “Take Dis Hammer.” I am glad I did not know that it was a song well known in Blues and Bluegrass circles. If so, I might have stopped there with a rendition offered by Lead Belly or Odetta, or Flatt & Scruggs. Or one of a dozen other versions done by blues artists over the last 80 years. But because I found it in the archives of The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress and in a Lomax field recording first, that was what I listened to.

I was moved by the voices I heard in those old John Lomax recordings, from a prison yard in Florida in 1939. He captured something powerful. As I listened, I imagined things that had not yet transpired when these songs were recorded. Nelson Mandela on a chain gang in a prison yard on Robben Island, in South Africa. Mohandas Gandhi and the peak of the Satyagraha movement, Martin Luther King Jr. and the marches, rallies and movements for Civil Rights yet to emerge. Black Lives Matter, and so much more.

John A. Lomax was a pioneering and visionary musicologist. Much of what we know about American Folk music from various eras before recording technology was accessible to most people, is because of John Lomax, his wives Bess & Ruby and his sons John Lomax Jr., Alan Lomax and daughter Bess Lomax. They transcribed by hand, and made field recordings of countless songs in a multitude of genres, preserving the musical styles that were endemic to certain regions or trades, or cultural sub-sets. And the Library of Congress Folk Archives are a true treasure trove of the extraordinary, including but by no means limited to the Lomax Collections.

John A. Lomax co-founded the Texas Folklore Society at the University of Texas in Austin in about 1908. The date is disputed, but in 1909, he nominated co-founder Professor Leonidas Payne to be President of the society. John A Lomax went on to help found Folklore Societies across the United States. His direct mentor at Harvard (which was at the time the center of American Folklore Studies, a field of study considered a subset of English Literature) was George Lyman Kittredge. Kittredge was a scholar of Shakespearean Literature and of Chaucer. He had inherited the position of Professor of English Literature from none other than Francis James Child. Child is known for his 8-volume lifetime work: Popular Ballads of England and Scotland. The work was unfinished at the time of Child’s passing, and Kittredge finished the work as well as continuing to teach several of the courses Child had taught. Lomax had a fine pedigree in sound research methods, and was likely the first to transcend the idea of American Folklore as a subset of English Literature and thus is appreciated in many circles as the progenitor of a new discipline: American Folklore a.k.a. American Ethnomusicology.

In 1910, Lomax published: Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, with a forward by none other than the recently retired President of the United States and aficionado of the American West, Theodore Roosevelt. It was quite a feather in the cap of a relatively young Lomax. But his truest musical love were songs that rose out of African American culture. And he was soon to find his way into the pursuit of many more forms of American Folklore. Lomax was the first to present papers to the Modern Language Association about American Literature in the form of uniquely American Ballads and Songs. He took to the lecture circuit while continuing to teach, publish, and make field recordings eventually with the help of his sons Alan and John Jr., and daughter Bess. Spanning several decades, John Lomax contributed over ten-thousand recordings to the Archive of American Folksong, at the Library of Congress.

At first the recordings were in the form of transcriptions and transliterations of the oral traditions he encountered. Old school. Lomax wrote them down. But as recording technologies improved and became more portable, Lomax was always on the leading edge of the latest capacity to record. In 1917, he was let go from his university position in Texas, over broader political battles within the institution, and was forced to take a job in the banking industry for several years in Chicago. But he became life-long friends with poet Carl Sandburg while he was there, and is referenced many times in Sandburg’s book Songbag (1927). In 1925, Lomax moved back to Texas to work for a larger bank there, but obviously being in banking became disastrous in the fall of 1929. In 1931, his beloved wife Bess Lomax died at age 50, and Lomax also lost his job when the bank for which he worked, failed as a result of The Great Depression.

In 1933, John A. Lomax got a grant from the American Society of Learned Studies and acquired a state-of-the-art phonograph, an uncoated aluminum disc recorder. At 315 pounds, he and Alan mounted it in the trunk of the family Ford sedan, and went off adventuring. John was finally able to pursue the archiving the musical and narrative memory of a quickly passing generation of African Americans. Many of his subjects were in prisons, but that was by no means the sum of his contact with the African American community. He did however recognize that Jim Crow and other racist practices had created a situation where a disproportionate number of African American men were imprisoned. And because many had been there for a long time, they had not been influenced by radio and recordings. The oral traditions were still alive in the prisons of the south in particular, and in ways that they were no longer present in other parts of the country.

It was in one such prison that Lomax met Lead Belly. And while many have accused John Lomax of somehow misappropriating ideas from Lead Belly, history from many angles suggests that Lomax was a staunch advocate for Lead Belly. Lomax advocated earnestly for Lead Belly’s release from prison, and while causality is hard to trace, Lead Belly was in fact released in August of 1934. The Lomax Family helped Lead Belly get work singing African American songs throughout the North Eastern US, and with the advice of legendary Western singer Tex Ritter, also helped Lead Belly get his first recording contract. John Lomax and Lead Belly had a falling out over the managing of finances in 1935, and never spoke to one another again. Alan Lomax however, remained a stalwart friend and an advocate of Lead Belly’s for the next 15 years, until Lead Belly’s death in 1949.

Though it is not clearly documented, it is very likely that Lead Belly himself learned Take Dis Hammer from the Lomax field recordings. He however only sang a few of the traditional verses, and invented his own version. He was prone to personalize many of the songs he sang and recorded, and was known to embellish on the historic record from time to time if it made a good story. In short, he was a Folksinger and Bluesman in good standing.

My version of Take Dis Hammer was derived mostly from the field recordings made by John, Alan, and Ruby Terrill Lomax, John’s second wife. There was no available transcription of the original field recordings which were made in 1939 at the Florida State Prison known as Raiford Penitentiary. These recordings were part of a series from the Southern States Recording Trip. So I listened, and listened, and listened again, at least 100 times. And I still could not discern certain words and phrases.

So, I spoke with Jennifer Cutting and Dr. Stephen Winick (with whom I am occasionally confused in public gatherings and always take it as a compliment) at The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. I explained the problem in trying to resurrect the original recorded version. They responded kindly that I should consider recovering as many of the original words as possible, and use my knowledge of the idiom, the period, and my capacity as a songwriter to fill in the gaps. So, I did. I also included a re-write of a verse that I traced to one of the Flatt & Scruggs recordings, and as a proper homage, I included a slight adaptation of one of Lead Belly’s verses. But the last verse was largely unintelligible. As such, I lifted what I could and made up the rest with knowledge of the context. Words I wrote to infill for inaudible words, or just invented to fit the context are italicized and in bold.

Much to my honor and delight I was asked to expand my research and offerr a longer program for the 2020 Homegrown Concerts (September 2nd, 2020) sponsred by the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. I resurrected and researched a dozen additional recordings from those three days in Raiford, and chose four of those additional songs for a presentation on the songs from the Raiford Prison (FL) in 1939. I engaged in what I will call anthropological songwriting where necessisary, to fill in the gaps in the verses or narrative. Lyrics and notes below, as well as links to the origianl field recordings that were my primary reference material.

You can listen to the "concert" here: https://www.loc.gov/concerts/folklife/joe-jencks.html

Do yourself a favor, troll around the Library of Congress Folk Archives and the Archive of American Folksong. But be forewarned, you will definitely get delightfully lost.

~ Joe Jencks

9-2-20

Take 'Dis Hammer / Take This Hammer

Raiford, Florida, June 4 1939

*Italicized bold lyrics written by Joe Jencks, based on the original Lomax recording

**Recorded on a Sunday – which was a frequent Visiting Day

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000582/

Take this hammer, hammer and give it to the captain

Take this hammer, hammer and give it to the captain

Won’t you Take this hammer, and give it to the captain

(Won’t you) Tell him I’m gone, Lord tell him I’m gone

And if he asks you, asks you was I running

And if he asks you, asks you was I running

And if he asks you, asks you was I running

Tell ‘m I was flyin’, Lord I was flyin’

Captain, captain this ole hammer too heavy

Captain, captain this ole hammer too heavy

Captain, captain this ole hammer too heavy

For the likes of man, for the likes of man

Must be the hammer, hammer that killed John Henry

Must be the hammer, hammer that killed John Henry

Must be the hammer, hammer that killed John Henry

But it won’t kill me, no it won’t kill me

This ole hammer, hammer shines like silver

This ole hammer, hammer shines like silver

This ole hammer, hammer shines like silver

But it rings like gold, lord it rings like gold

Flatt & Scruggs Bluegrass Verse ~ NOT used

I don’t want, your old darn shackles

I don’t want, your old darn shackles

I don’t want, your old darn shackles

‘Cause it hurts my leg, ‘cause it hurts my leg

Odetta Verse ~ NOT used

I don’t want your cold iron shackles

I don’t want your cold iron shackles

I don’t want your cold iron shackles

Around my leg boys. Around my leg.

Joe Jencks Adaptation – more in keeping with the original Prison Yard cadence and language

Don’t you make me wear, wear these old cold shackles

Don’t you make me wear, wear these old cold shackles

Don’t you make me wear, wear these old cold shackles

‘Cause they wound my soul, Lord they wound my soul

Lead Belly Verse… JJ Adaptation to meet cadence of Prison Yard

Twenty-five miles, alone in Mississippi

Twenty-five miles, alone in Mississippi

Twenty-five miles, alone in Mississippi

Tell him I’m gone, oh Lord tell him I’m gone

Joe Jencks Verse – best guess based on cadence and audibility of

Lord I’m coming, to that Jordan water

Lord I’m coming, to that Jordan water

Lord I’m coming, to that Jordan water

Don’t you let me drown, Lord don’t let me drown

We Don’t Have No Payday Here

Raiford, Florida, June 4 1939

*Italicized bold lyrics were written by Joe Jencks, based on the original Lomax recording

**Recorded on a Sunday – which was a frequent Visiting Day

***Ruby was not allowed in the Men’s Dorm – so she went to Services in the Women’s Dorm and got the recording machine into the Women’s Dorm Chapel for the Sunday Service

****Joe Jencks based added lyric content for this song on recurring themes from other prison songs and spirituals of the time, and on the recorded cadence of lyric, even if the precise lyrics were not audible.

*****“Cry ‘bout a nickel, die ‘bout a dime” also appears in “I’m Goin’ Where The Sun Never Shine”

****** “Pay Day” has the same melody and cadence as “You Must Be Born Again”

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000584/

We don’t have no pay, have no payday here

We don’t have no pay, have no payday here

And it don’t worry me

That it all, oh Lord, ain’t mine (That I don’t [Lord] have a dime)

We don’t have no pay, have no payday here

Sugar I’ll be home someday

Sugar I’ll be home someday

And it may be June, or July, or May

Sugar I’ll be home someday

Lord I wonder who gonna welcome my right name

Lord I wonder who gonna welcome my right name

And it don’t worry me

That it all, oh Lord, ain’t mine

Lord I wonder who gonna welcome my right name

I guess you know my mind

I guess you know my mind

Then you cry ‘bout a nickle

And you die, honey, for a dime

I guess you know my mind

Well, I’m goin’ up where, where the sun gone’ shine

Well, I’m goin’ up where, where the sun gone’ shine

And my soul surly know

That my home is where I’ll go)

Well, I’m goin’ up where, where the sun gone’ shine

We don’t have no pay, have no payday here

We don’t have no pay, have no payday here

And it don’t worry me,

That it all, oh Lord, ain’t mine

We don’t have no pay, have no payday here

Trouble Is Hard

Raiford, Florida, June 4, 1939 – sung by Gussie Slater (Slayter) & the Women in the Raiford Women’s Dorm

*Italicized bold lyrics were written by Joe Jencks, based on the original Lomax recording

**Recorded on a Sunday – which was a frequent Visiting Day

***Ruby was not allowed in the Men’s Dorm – so she went to Services in the Women’s Dorm and got the recording machine into the Women’s Dorm Chapel for the Sunday Service & additional recording on that day.

**** Ruby typed verses to this song in a different order than was on the recording. This text reflects the recording.

***** Joe Jencks found a song recorded earlier on the Southern States Recording trip at a prison in TX called, “Two White Horses.” It must have been a commonly known song of the times, and a common point of reference for someone, perhaps from TX, who had been incarcerated in Raiford.

****** As a result of recording in a mor epristine environment, I suspect Ruby captured better quality audio. As such Trouble Is Hard and Battle Ax were among the most audible of the field recordings from June 2-4 at the Raiford State Farm.

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000660/

My trouble is hard, so hard

My trouble is hard now, so hard

My trouble is hard, so hard

Lord, I just can’t believe my trouble is hard

Well down by the graveyard, I’m gonna walk

Me and God almighty, gonna have a little talk

Two white horses, side by side

Me and God almighty, gonna take a ride

Oh stop young man, I’ve got something to say

Oh, you are sinnin’ why don’t you pray

Sinnin’ against and in vain of God

Who has power to slay us all

Well God called Moses on the mountain top

And stomped his Laws in Moses heart

Placed his commandments in his mind

Go, Moses don’t you leave my lamb behind

Well “A” for Adam, and he was a man

Placed in the garden that God command

Adam was the father of the Human race

He vi’late the law, and God throw him from the place

Well Adam went away, he didn’t stay long

Before God sent him, a savior come

He overtook Adam, and he caught him by his mind

The fire will reach him just in time

Well go down angels, consume the flood

Blew out the sun and turned the Moon to Blood

Come back angels and bolt the door

The time that’s been, won’t be no more

Oh Ye Prodigal Son

Raiford, Florida, June 2, 1939

*Italicized bold lyrics were written by Joe Jencks, based on the original Lomax recording

**Recorded on a Friday – which was less common. John A. Lomax more frequeltly recorded in prisons on Visiting Days (Sundays)

***Singular in the Raiford recordings in the precise clarity and sophistication of the harmonic structure.

****Joe Jencks wrote more lyric content for this song than some, based on recurring themes from other prison songs and spirituals of the time, and on the recorded cadence of lyric, including the middle verse.

***** Ruby Terrill Lomax typed the last verse in her field notes (perhaps based on John's hand written notes), but it was not on the recording which consisted only of the chorus and 1st verse.

****** The groove of this song on the field recording was very reminiscent of Motown; a musical style that would not emerge in popular culture for nearly another quarter of a century.

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000485/

Oh ye prodigal son

Oh ye prodigal son

Oh ye prodigal son

Go and be a servant of the Lord

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

And be a servant, of the Lord

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

Oh, I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

And be a servant, of the Lord

Was a Prodigal Son, he was a fall away child

A Father he wouldn’t obey

Well he left, so he left his father’s house

He thought he was a goin’ astray

Oh, I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

Oh, I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

And be a servant, of the Lord

He was sleepin’ at night in a stable bare

Beggin’ by the side of the road

Wishin’ only to be in his father’s house

Oh, just to carry a servant’s load

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

Oh, I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

And be a servant, of the Lord

His father saw him comin’

And he met him with a smile

He threw his lovin’ arms around him

Cryin’ “This is my darlin’ child!”

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

I believe it, I believe it, I will go back home

And be a servant, of the Lord

He’s A Battle Ax

Raiford, Florida, June 4, 1939 – sung by Gussie Slater (Slayter) & the Women in the Raiford Women’s Dorm

*Italicized bold lyrics were written by Joe Jencks, based on the original Lomax recording

** Penumtimate verse written by Joe Jencks based on the Genesis 18:8-15 narrative referenced in the verse about when Mary (Mother of Jesus) “knocked on Abraham’s door”

***Last verse in Ruby’s Notes – but not on recording

****Recorded on a Sunday, which was a frequent Visiting Day in prisons and "state farms."

*****Ruby was not allowed in the Men’s Dorm – so she went to Services in the Women’s Dorm and got the recording machine into the Women’s Dorm Chapel for the Sunday Service.

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000565/

He’s A Battle Ax

In the time of a Battle

He’s A Battle Ax

In the time of a Battle

He’s A Battle Ax

In the time of a Battle

Shelter in a mighty storm

Well Can’t no man do like Jesus

Not a mumblin’ word he said

He just walked right down to Laz’rus Grave

And raised him from the dead

Well Easter night, he started back home

He stopped in Jerus’lem while pressing along

Folks heard a Doctor’s got more treasures than gold

Doctor can you feed a dying soul

Well, had it not been for Adam

There would not have been no sin

Oh, Adam broke the laws of these commands

Now we got a debt to pay

When Mary was seeking for religion

She was only 12 years old

She was skipping over hills and knocking

She knocked at Abraham’s Door

Just like Abraham and Sarah

Mary had her a lovin’ son

She brought to the world a savior

And now every battle’s won

Well A is for Almighty that’s true

B is for Baby like I (me) and you

C is for Christ, sent from God

D is for The Doctor, Man of All